Charles Cantalupo, distinguished professor of English, comparative literature, and African studies, speaks about his newest book at a launch party hosted at Penn State Schuylkill.

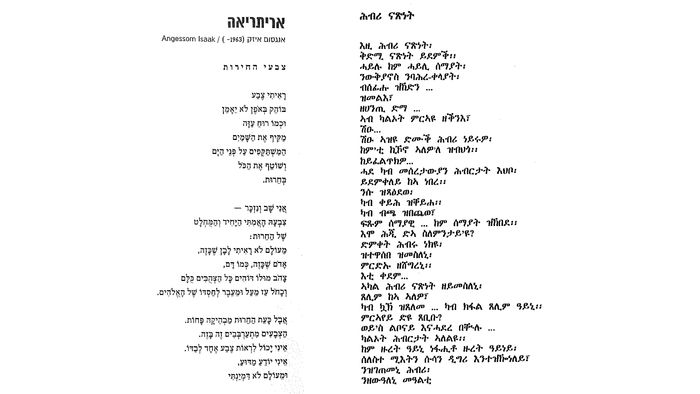

SCHUYLKILL HAVEN, Pa. — Charles Cantalupo, distinguished professor of English, African studies, and comparative literature at Penn State Schuylkill, has been translating African poetry for two decades. In 2005, he translated a poem titled “Freedom’s Colors,” and now, that English translation acts as the intermediary between the poem’s African origin and its new Hebrew translation.

“Freedom’s Colors” was penned by Eritrean Angessom Isak. Eritrea is a northeast African country, bordering the Red Sea. Its location is important to Cantalupo’s work — most nations in the Horn of Africa speak myriad languages, including indigenous languages and the languages of many a colonial power whom the region has seen come and go. Eritrea, for instance, has at least nine languages, in addition to the Italian and English left behind by previous colonizers of the country.

“Still, the people maintained their own native languages,” said Cantalupo. “They recognized their native languages as a source of tradition, wisdom and social mobility.”

When Ghirmai Negash, professor of English and postcolonial literatures at Ohio University, paired with Cantalupo to translate Eritrean poetry, they tackled works written in one of the nation’s native African languages: Tigrinya. They compiled their translations and released a book of poetry titled "Who Needs a Story?" which included translations of contemporary Eritrean poems originally written in Tigrinya as well as in Tigre and Arabic.

When written, Tigrinya is composed of an ancient script known as Ge’ez. According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, Ge’ez evolved in Ethiopia — one of Eritrea’s neighbors — and was initially used in the church. The oldest known Ge’ez inscription dates back to 500 CE and, though Ge’ez itself is no longer a popular, spoken language today, its glyphs found a home in modern Africa.

Cantalupo pointed out the similarities between the original poem written in Ge’ez and the Hebrew translation. Hebrew originated in Israel, and Israel’s proximity to Eritrea explains those similarities.

“Ge’ez has the same language root as Hebrew. They are both Semitic languages,” explained Cantalupo, sketching a map of the Horn of Africa and its middle eastern neighbors. “And Ge’ez is the ancient script of a number of African languages. If one compares the Ge’ez and Hebrew scripts, they even look similar.”

“The translation of a poem from one language into another can never be merely direct or literal,” Cantalupo said as he recounted the last 20 years he has devoted to this work. “That’s not possible, nor is it even desirable."

The most important task Cantalupo meets when translating poetry is to try to create as great a poem in English as in the original language. To do so, he said, “The translation is not nor is intended to be an equivalent.”

When he first began translating poetry, Cantalupo focused on one author. Today, he translates poetry from many African-language poets. Furthermore, he never expected to write about war but felt obligated to amplify the voices of peoples affected by colonialism and seemingly ceaseless civil war and disorder.

“It can seem more difficult to govern than to win a war,” said Cantalupo, describing Africa’s literature and the indelible impact war has made on it.

In the short time following the publication of the Hebrew translation of “Freedom’s Colors,” Cantalupo’s translations have evolved once more. This time, his translation of a poem by Reesom Haile, titled “Knowledge,” has been converted to Tamil. An excerpt from the same poem, moreover, was engraved on a wall of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in Seattle.

Cantalupo said he hopes his translations connect people across different eras and throughout the world, magnifying voices that have been unheard until now. For readers looking to learn more about war and peace in Africa, a multitude of translations awaits.