SCHUYLKILL HAVEN, Pa. - Art Zilleruelo, assistant teaching professor of English and co-coordinator of the Honors Program at Penn State Schuylkill, has long been fascinated by nature and the mingling of terror, beauty, and reverence he experiences in its presence. From his youthful wanderings along the banks of the Susquehanna River to his current excursions into the wilderness of poetic composition, Zilleruelo has long pondered the human experience in the natural world.

Born and raised in Northumberland and Schuylkill counties, he spent a good part of his childhood and adolescence exploring the region’s woods and riverbanks. Even as his graduate education took him first to the Midwest, and then to New England, his fascination with nature and the human connection to the natural world deepened.

“The Massachusetts North Shore, where I resided when I was a graduate student, stands out in my memory as the haunt of a particularly tangible genius loci, or spirit of place” recalls Zilleruelo. “It’s partially to do with the Atlantic: it doesn’t feel like a body of water. It feels like an amorphous living entity, an entire atmosphere, that envelops the whole of the coastal region and penetrates halfway down the state. Even now, half a decade since I last lived there, I feel a pronounced yearning for the North Shore, an undeniable, magnetic pull towards the place.”

Zilleruelo continued, “That capacity for appreciation and fascination was cultivated during my formative years here in Pennsylvania. Spending so much of my youth immersed in the (mostly) unspoiled environment of the Shenandoah Valley allowed me to cultivate (organically, without conscious intent) an appreciation for both solitude and the ‘company’ of flora and fauna.”

In the beginning

Zilleruelo first began a serious study of poetry while an undergraduate at Penn State Schuylkill under the tutelage of Charles Cantalupo, distinguished professor of English, comparative literature, and African studies. It was during this time that he discovered a tradition of like-minded poets who also drew inspiration from the untamed richness of the natural world.

“I immediately gravitated towards poets who valued, respected, and even feared nature, especially British Romantics like Wordsworth and Coleridge, and late Modernists like Ted Hughes,” explained Zilleruelo. “Wordsworth’s 200-year-old accounts of having been aesthetically educated by often terrifying confrontations with nature felt uncannily familiar and inexplicably, anachronistically contemporary to me. I recognized in Wordsworth’s best poems elements of my own growth into an awareness of some natural agency or ontic force he calls the ‘presence’.”

“And I have felt / A presence that disturbs me with the joy / Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime.”

-- William Wordsworth. “Lines Written (or Composed) a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye During a Tour, July 13, 1798”

Zilleruelo’s work continued to excavate the human connection to the natural world, and he found a deep affinity for this tradition of poetry that examines the natural world with the vocabulary of the profound, unknowable, and mysterious — voicing nature as a source of beauty, inspiration, and solace, but also a source of discomfort and unease.

Climate, class, and consumption

In recent work, Zilleruelo has also used a poet's pen to dissect the concept of "consumption" and human complicity in what he refers to as the “exploitative consumerist systems” that have come to define life in the 21st century.

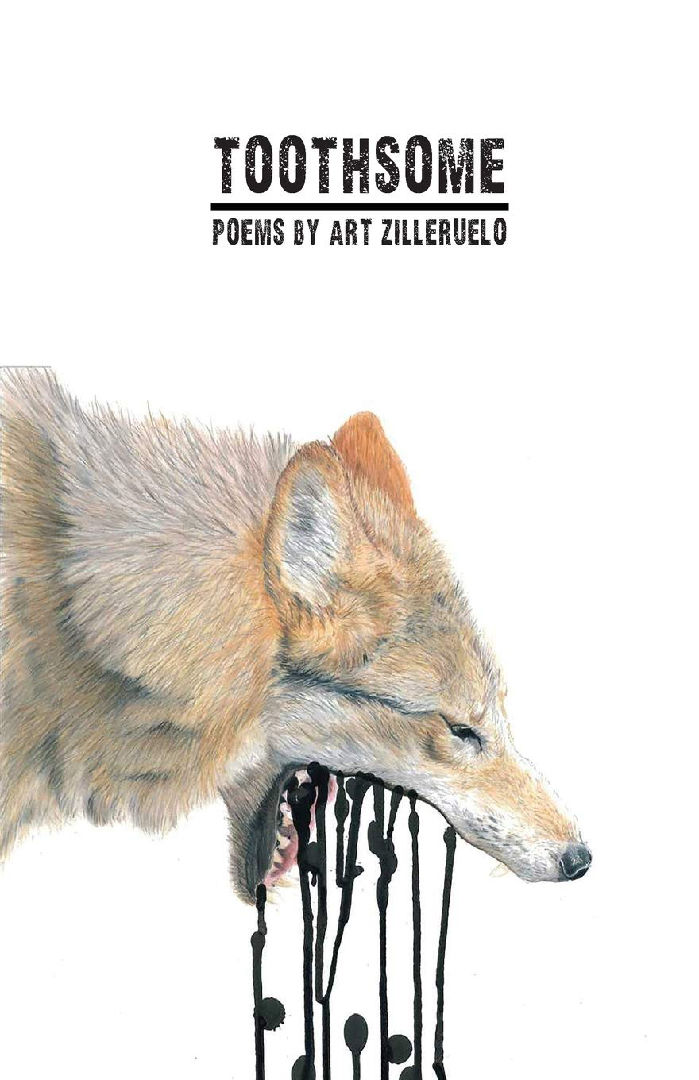

In his latest collection of poetry, "Toothsome" (Spartan Press, 2020), Zilleruelo considers global capitalism through the lens of various contextual motifs — from economically devastated towns in anthracite coal country to apocalyptic vignettes of the planet in climate crisis. As in previous works, he draws on a familiar sub-theme: how human language is both a powerful and limiting tool for how we, as humans, both understand and describe the natural world.

We caught up with Zilleruelo recently to talk to him about poetry, the climate crisis, and his new book.

Q. First, why poetry?

A. Before Modernism, poetry could achieve many effects that prose could not — or, more precisely, had not. Poetry was thought to be more musical, more powerfully infused with emotion, and otherwise removed from the utilitarianism of prose. However, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, William Faulkner and the other High Modern novelists and short story writers daringly expanded the aesthetic and expressive palette of prose. Consequently, poetry was left with little that it could truly call its own.

The exception is the poetic line: the line broken not arbitrarily when words reach the margin of the page, but broken intentionally when the poet determines a break can make the words register with a specific music or meaning to the reader.

When I write poems, I try to remain vigilant as the lines take shape…I strive to write lines that exist in a state of musical or semantic tension with the lines that surround them. I want my poems to feel like at any moment, they might unmake or unweave themselves by succumbing their internal tensions, but somehow they find a way to maintain their precarious hold on whatever harmony they manage despite the always-lurking threat of dissonance.

Q. How does Toothsome expand or differ from your previous work?

A. In some respects, Toothsome represents a continuation of what I explored in "The Last Map" (Unsolicited Press, 2017). That collection consisted almost exclusively of poems that addressed the relationship between nature and language. The great paradox of that relationship is that we can usually only understand nature the same way we understand everything else: by filtering it through language and concepts. Nature, however, cannot always be constrained by the words and ideas we use to approximate some understanding of it. The current climate crisis is a consequence of our failure to remember that our metaphors for nature are merely rhetorical efforts to make nature what we want it to be instead of accepting it for what it is.

The Last Map aspired to a comprehensive account of unaccommodated nature in its many aspects, but Toothsome zooms in on the more savage quadrants of The Last Map, and it tracks the expansion of this savagery out of nature and into industry, politics, and whatever else we have convinced ourselves represents our transcendence of nature rather than confirming our repetition of its cruelest patterns.

Q. Tell us more about some of the themes in Toothsome.

A. The poems in "Toothsome" (Spartan Press, 2020) explore “consumption” in both major senses of the word. These poems bear witness to a) the horrors of human and nonhuman animals as they both devour and are devoured in service to the universal biological imperative to feed, and to b) the manufactured, engineered horrors of global capitalism in the Anthropocene [the current geological age, during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment].

One important sub-theme is the role of language in both instantiating and resisting the influences that consumption and consumerism have upon our lives. These poems seek to trace to their logical conclusions the implications of the etymological connections between corpus, corpse, and corporation.

Q. How does your work dovetail with what you are teaching in the classroom?

A. A strong secondary inspiration throughout my work is my increasing anxiety about the climate crisis, and that has infiltrated the topics that I cover in the classroom. Last semester, I had the privilege of teaching a section of GEOG 2N: Apocalyptic Geographies, and we devoted an entire study unit to exploring climate change and its likely effects. I also taught a sustainability-themed section of ENGL 15: Rhetoric and Composition.

A theme that we encountered frequently in our readings and discussions for both courses was the idea that climate change could be read as a metaphor for divine retribution: that nature had patiently endured the injuries and insults we inflicted upon her for centuries and now had no choice but to visit a kind of cleansing damnation upon us.

A very late addition to "Toothsome" was a poem I called “Whatever Augury,” a long, contemplative narrative poem that explicitly explores how climate change affects our region and how this metaphor of divine retribution might shape our personal and political responses (or lack of responses) to climate change. I had written it before I began teaching these courses, but some encouraging words from Honors students who heard the poem (when I had the pleasure of reading with Dr. Cantalupo at our annual Honors Program poetry reading) lent me the courage to include it in the manuscript.

Q. Do you have any readings or book promotions scheduled?

A. Under normal circumstances, poets schedule readings on college campuses, at libraries, and at bookstores to promote their new collections. Raising awareness about one’s work in the middle of a pandemic is somewhat more challenging... I’m still working on putting a virtual reading together with a few other poets who have also had new collections published recently. Whenever delivering conventional readings becomes viable again, I’ll do a belated book tour, and I hope that includes a reading here on the campus of Penn State Schuylkill.

"Centralia"

Published with permission of the author

Who now can doubt that the earth hides fires,

that the land can speak through many mouths,

that some dark mountain husbandry

has converted this forest to a larder

and these fields to an oven?

Zilleruelo, A. (2020). Toothsome. Spartan Press

Follow Art Zilleruelo, or read his latest offering, Toothsome (Spartan Press, 2020), available online at Bookshop, or at the Penn State Schuylkill Bookstore.